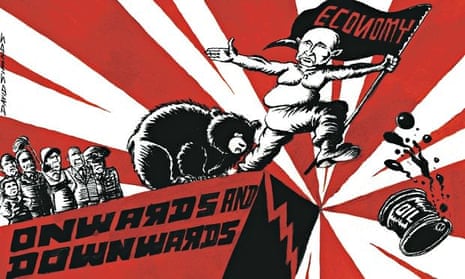

Vladimir Putin had his Jim Callaghan moment last week. Faced with questions about the state of the economy in the wake of the rouble’s freefall on the foreign exchanges, the Russian president said the problems would be overcome in two years. Echoing Callaghan’s words on his arrival back to the UK from a summit in Guadeloupe during the winter of discontent, Putin said it was not even fair to say Russia was in crisis.

Given some of the previous setbacks Russia has overcome, that may well be true. It is not like 1941, when the country’s very existence was in doubt. It is not like Stalin’s manmade famine in the Ukraine in 1932-3. But by the standards of the modern world, Russia is facing a crisis. Even before last week’s turbulence on the foreign exchanges, the central bank was expecting the economy to contract by 4.5% next year. A deep recession is unavoidable.

Putin’s optimism about the economy is based on the assumption that the global price of oil will rise as cheaper energy prices spur consumer spending and investment across the world. He’s almost certainly right about that. Booms are nearly always associated with low oil prices, so there is a good chance that global GDP will be higher than expected next year. That will lead to higher demand for oil, which will push up the price. Some analysts think the recent fall in the cost of crude has been overdone and that the price will recover to about $80 a barrel next year.

In the short term, this would be good for Russia, given its dependence on the energy sector. In the long term, though, it would be better for Russia if the oil price stayed low: that would force the country to tackle some of the economic challenges it has ducked for the past couple of decades.

Here’s the problem. Russia is a resource-rich country. It has abundant oil and gas reserves. It has big mineral reserves and large forests. What Russia doesn’t have is a modern manufacturing sector. Its industrial base is old and uses clapped-out equipment. It has failed to invest in either physical or human capital. So 80% of its exports are in oil, natural gas, metals, timber and defence equipment.

The make-up of the economy has changed little since Russia’s last brush with the financial markets, in 1998. What happened then was that so much capital was leaving Russia that the country had to run a big surplus on its current account – exporting more than it imported – in order to keep the balance of payments stable. A low oil price made this impossible, and a rising balance of payments deficit led to a run on the rouble. Bringing the balance of payments back into line required a dose of heavy domestic austerity designed to restrict imports.

That should have been a lesson to Moscow’s policymakers. But they did nothing, and from 2003 onwards rising oil prices papered over the cracks. With the cost of crude above $100 a barrel, Russia could run both a budget and a current account surplus. It didn’t seem to matter that the economy was becoming ever more narrowly focused on the energy sector.

But now that the oil price has fallen – from $115 a barrel in the summer to around $60 a barrel on Friday – the old problems have come back. A smaller current account surplus is not big enough to cover losses on the capital account, which are estimated to be around $125bn this year.

That’s why the rouble has come under pressure and why, in the absence of a sustained effort to rebalance and modernise the manufacturing sector and invest in new machinery and skills, it will keep on coming under pressure every time there is a sustained fall in the cost of crude.

Stressful times for the Co-op

Let’s be frank. House prices have never fallen as far as 35% during a recession, so when the Bank of England said last week that its stress-test scenario had gauged how well lenders could cope with a serous shock, it had a point. Of the eight lenders tested, those with relatively large mortgage books – Nationwide, Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds Banking Group and Co-operative Bank – would be particularly exposed if such a calamity were to take place.

The embattled Co-op Bank had trailed its failure in advance, but the scale of it was spectacular. As the Bank of England put it, Co-op Bank’s capital would be exhausted. In simple terms, the bank would be wiped out. But RBS and Lloyds – already backed by the taxpayer – would also take a hit, and policymakers made it clear that the two banks needed to stock up on capital to be safe.

That is all well and good, but on the day the Bank of England was releasing the results, the financial market’s anxiety about house-price bubbles had abated, to be replaced by fears that a full-blown currency crisis is under way in Russia.

So it is right that next year’s test will focus on risks in emerging markets – then Standard Chartered and HSBC might find themselves in the spotlight. But it is a shame that the Bank of England stepped back from extending its stress tests further across the financial system, to foreign banks with big presences in the City that could be exposed to market turbulence. It should return to this idea in the future.

In the meantime the focus is on the Co-op Bank, which is being shrunk to fit its capital and expects to remain loss-making until at least the end of 2016. Not so long ago, the Co-op was being positioned as a major challenger bank to the big four of RBS, Lloyds, Barclays and HSBC. The chances of that now look pretty slim. The stress-tests results provided yet another reminder of the corporate governance disaster that unfolded at the bank and its former parent, Co-operative Group.

Did you hear the one about the two Irishmen in an airline office?

The prodigal son of Aer Lingus may return. And this time, he could be buying up the homestead. Willie Walsh, boss of IAG, the group formed to wed British Airways to Iberia and any more European airlines it fancied, has turned his sights on the Irish airline at which he first entered the business. Back in 1979, he was a starry-eyed pilot. By 2001, having briefly flown the nest to run a Spanish charter business, he was the chief executive earning a reputation as a brutal pruner of jobs. “Slasher” Walsh did the same at BA, then at Iberia.

Aer Lingus staff can probably rest easier. The business is already lean and profitable: its biggest single shareholder is Ryanair. An IAG takeover would see Walsh playing hardball with Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary. It would be some battle. Two famously rich and proudly tight Irishmen. Who will prove the meanest?