US-China tech war to be ‘defining issue of this century’, despite signing of phase one trade deal

- Trade deal and tech war are in ‘parallel universes’ with minor progress on tariffs a mere sticking plaster in wider deterioration, academic says

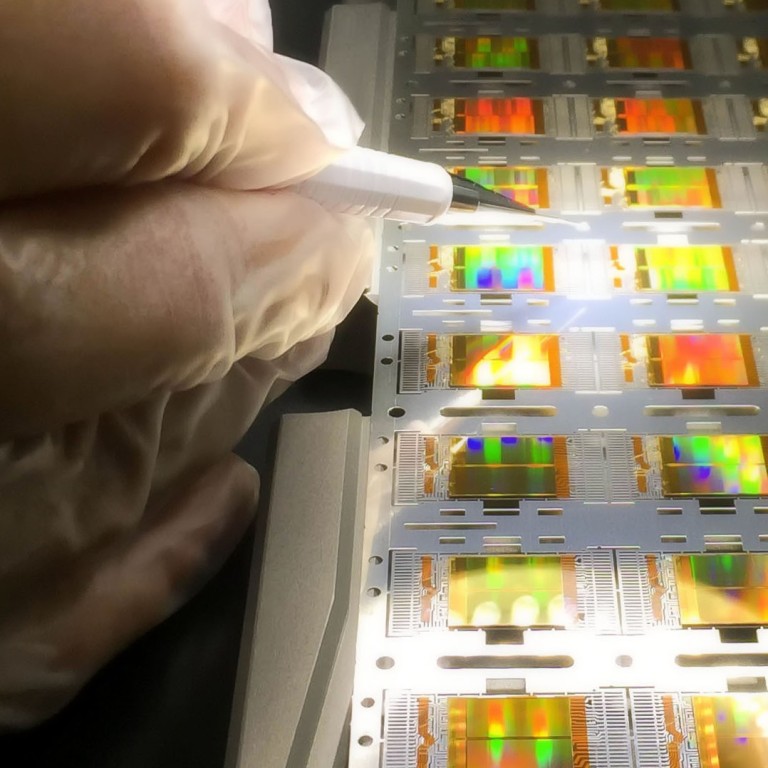

- Report states that decoupling is inevitable in the crucial semiconductor space, with a ‘new era of techno-nationalism’ set to shake up global value chains

That is the message contained in a new report to be released on Monday, the author of which says that tariffs are “a subset in a much larger, overarching, systemic rivalry between two superpowers, which is the defining issue of this century”.

Capri wrote the report, subtitled How a New Era of Techno-Nationalism is Shaking up Semiconductor Value Chains, for Hong Kong’s pro-trade Hinrich Foundation. It says we are in “a new strain of mercantilism that links tech innovation directly to economic prosperity, social stability and to the national security policies”.

“Even if the two superpowers are able to repair ongoing trade tensions and hammer out a series of trade deals, there will be no turning back from the pervasive effects of techno-nationalist policies,” read the report.

Even while pursuing a trade accord on one hand, the US has been actively trying to reduce technological integration with China on the other.

As US President Donald Trump and China’s Vice-Premier Liu He were signing the phase one deal in the White House, the US was lobbying Britain to ban Huawei from its “critical national infrastructure” and considering plans to invest at least US$1.25 billion “in Western-based alternatives to Chinese equipment providers Huawei and ZTE”.

The trade deal, which is focused on tariffs, is in a completely different space. These are in parallel universes – we have tariffs on one side then we have the US-China tech war on the other

This leaves more scope for authorities prevent perceived bad actors or rivals from acquiring their goods, while the US government has provisions – such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations – that can completely block the export of technology to designated buyers, at even the most minimal level.

“While there are changes to some Chinese technology policies, phase two is unlikely to make much progress in addressing the two countries’ rivalry,” said Chris Rogers, Research Analyst at Panjiva, S&P Global Market Intelligence.

While there are changes to some Chinese technology policies, phase two is unlikely to make much progress in addressing the two countries' rivalry

The US, meanwhile, owns 45 per cent of the global market share in semiconductors, with Korean firms in second place accounting for 24 per cent. Government efforts to decouple the tech economies of the US and China will therefore hurt American firms that are dominant in the Chinese market.

“More than 60 per cent of Qualcomm’s revenue came from China in the first four months of 2018; for Micron, over 50 per cent; for Broadcom about 45 per cent,” read the report.

A ban on Huawei buying US tech combined with the overall market uncertainty from the tech war led to Broadcom revising down its 2019 revenue estimate by US$2 billion.

However, given that the most advanced Chinese producers of semiconductor technology are two to three generations behind their US rivals, China would be the major short-term loser should decoupling continue, Capri said.

“It’s not a zero-sum game, in the long term everybody loses, but in the short term particularly when speaking of semiconductors, if you have the application of export controls applied by the US and EU together, and potentially by the Taiwanese, Japanese and others, the short term loser is absolutely China,” he said.

China, meanwhile, is searching for ways to become technologically self-sufficient, pumping tens of billions of dollars into its domestic tech sector, and looking to lure overseas developers to the mainland to help with the drive.

China is aiming to increase its reliance on domestic production for key components, including chips and controlling systems, to 75 per cent by 2025, the former minister said.