Spain housing: Evictions and broken promises in a pandemic

- Published

Evictions are an unwelcome fact of life in Ciutat Meridiana, one of Barcelona's poorest neighbourhoods. Even during the pandemic, the local residents' association meets weekly in the town hall, to hear from people who face losing their homes in the midst of a public health crisis.

A Spanish law last March was supposed to put a halt to evictions during the Covid-19 crisis.

"No-one in a tough economic situation will lose their home. In this crisis, no-one will be evicted from their home," promised Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez.

That proved not to be the case for the people of Ciutat Meridiana, where people continue to be served eviction notices. And campaigners say thousands more have been been evicted across Spain. This emotive issue has brought to the fore Spain's chronic lack of social housing and inflamed public debate around an individual's right to a home.

'Eviction town'

"The situation here is very, very, very bad," complains Filiberto Bravo, the head of the residents' association who's been fighting against evictions in the community for nine years.

We are a very small neighbourhood of around 10,000 inhabitants. Right now, we have a frequency of some four, five or six evictions every week

Cecilia, a mother of three young children, was served an eviction notice on 25 October that said her home would be repossessed by a bank a month later.

"Sometimes I want to cry. I think about my children, what will I do for my children if they kick us out of here tomorrow," she says. "I feel nervous at night. I can't sleep because I'm just going over it in my head, what's going to happen?"

Cecilia and her partner Carlos have been living in their apartment for four years. They were paying rent to the owner of the flat until one day he disappeared and stopped paying his mortgage.

She now wants to negotiate an alquiler social (social rent) with the bank that enables vulnerable families to pay reduced rent on a property, ranging from €150-€400 (£135-£360; $180-$480) per month, to a maximum of 30% of the total net income of the family unit.

The bank, however, would rather repossess the property. On 26 November Cecilia was told their eviction had been postponed, but the threat of repossession still hangs over the family.

"We're not asking to live rent-free. What we're asking for is social housing where I can live peacefully with my children," she says. "To not have this constant worry, knowing that at some point they will come back and they will try to evict us again."

The neighbourhood has become known in local media as "eviction town", due to the high number of repossessions in the area and the community's battles against eviction, week in, week out.

Politics of property

Cases like Cecilia's are common, according to Javier Crespo of grassroots organisation PAH Madrid, which is fighting against the evictions.

The problem, he believes, is that the government's ban on evictions during the Covid-19 crisis has been limited to people who can prove they have become vulnerable as a "direct consequence of the pandemic".

"It's very difficult for the courts to know why you're vulnerable in a given moment. Is it because of the pandemic, or were you vulnerable previously? That's the problem, the law saying evictions are forbidden is not true," he says.

Latest reports suggest the government, under mounting pressure from left-wing coalition partner Podemos, will soon pass a law banning eviction until May 2021, unless a decent housing alternative is available.

'No right of occupation'

Not everyone sees it this way. Illegal home occupancy has also been a big story under the pandemic. Opposition parties want to clamp down on it and Madrid's City Hall has announced the opening of an "anti-occupation office" to tackle criminal lodging.

"The right to access a house is of course a right in our constitution, but that doesn't mean you have the right to occupy or get into a private property," says Pere Joan Perete, a criminal lawyer who represents private property owners.

He argues that mafias are taking advantage of vulnerable families by breaking into empty buildings, changing locks, and selling the keys for around €1,000 to €2,000.

These mafias take advantage of the current situation in the real estate market and the lack of efficient public policies on housing, so these vulnerable people are an easy target

'Devastating impact'

While he believes that evictions should be made quicker and easier for property owners, Mr Perete agreed the government had a responsibility to make more affordable housing available to vulnerable families.

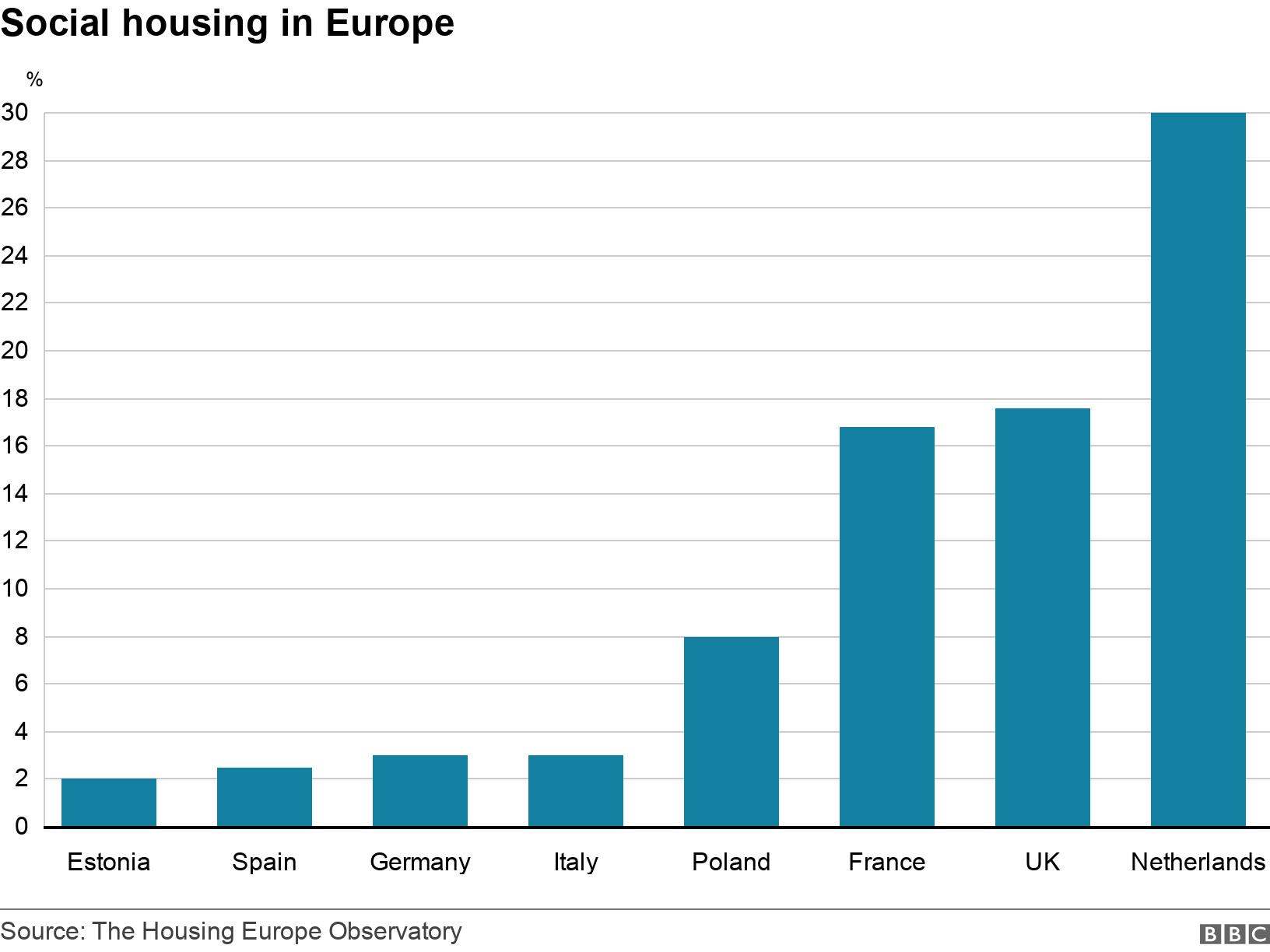

Social housing in Spain makes up just 2.5% of all residences and a 2019 report by Amnesty International said scarcity of social housing in Spain has had a "devastating impact" on low-income families.

Activists say the issue is compounded by the high number of homes owned by banks and investment funds that are left empty. This, they argue, contributes to the fact that Spain has one of the highest proportions of empty dwellings in the world.

The issue was thrust into the spotlight last week, when three people were killed in a fire at an abandoned industrial building that was being occupied in Badalona, a town outside Barcelona.

Catalan President Pere Aragonès told local broadcaster TVE that the incident was "a tragedy on top of the economic tragedy in which many of these people already found themselves."

Local administrations are now beginning to take action. In July, Barcelona's housing department wrote to 14 companies that collectively own 194 empty apartments, warning them the city would seize the properties if tenants weren't found within a month.

But measures like this have inflamed public debate over housing.

While to some Spain has become a squatters' paradise, others worry about a desperate lack of affordable housing. How the national government responds will have a significant impact on the most vulnerable.

Housing crisis: Could London learn from Europe's housing schemes?

With additional reporting by Eloise Edgington.

Related Topics

- Published12 December 2018