Thinking Things Over April 22, 2012

Volume II, Number 16: Monetary Policy, the Real Economy, and Asset Prices: Where are We?

By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Canton, Ohio.

In the wake of recent market volatility, and ahead of the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee meeting here on April 24-25, calls for another round of Fed easing, “QE3,” have again been stoked. It is worth sorting out the pros and cons of such a move for both the U.S. economy and financial markets.

What is Chairman Bernanke So Concerned About?

As the Federal Reserve staff prepares for this week’s meetings of the Open Market Committee, it is worth taking stock of the current situation from Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s perspective, now three years into economic recovery. Whether or not the prediction of some that 2012 will result in yet a new recession is correct or not, the U.S. economy remains sluggish, with various “headwinds” (particularly in Europe, China, Japan, and U.S. corporate investment slack) slowing its growth. The Fed Chairman himself, in a series of recent speeches at George Washington University, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and a conference in New York on post-crisis policy-making, has continued to lament the “elevated” unemployment and scattered prosperity, and ratified his staff’s long term projections of a dramatic decline in the rate of economic growth in the U.S. (from a long term average of 3.3% to a now-expected rate in the range of 2.4%).

Why has this long-term sluggishness set in, given extraordinary – and global – levels of spending stimulus, and equally historic levels of monetary ease and credit creation? These after all are the policies called for by Keynes, and advocated by the world’s leading living Keynesian, Princeton economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman (indeed, for Krugman, the magnitude of spending and money creation has not been nearly big enough).

In short, it is this very question that has captured the mind of Mr. Bernanke. For he well knows that as fiscal imbalances are enlarged via more indebtedness, the capacity for growth in an economy stalls, and can even decline (in the extreme), in periods of capital consumption. Mr. Bernanke also knows – but will never admit out loud – that in spite of all of the harangue about new economic leadership out of Asia, or the size and scale of the European Union, that for at least several decades more, global growth must be ignited, fostered, led, and sustained by the United States. That is to say, without strong and sustainable growth in the United States, there can be no real sustained recovery globally. What then are his options?

The Fed’s Dual Mandate and Resulting Monetary Policy

By statute, the Federal Reserve has a “dual mandate”: to preserve price stability as well as pursue full employment. In recent pronouncements the Fed has made plain that to the degree these come into any short term conflict, the bias will be toward stimulation of commerce, and the employment it begets. In truth, this has been the policy preference of the Bernanke Fed since nearly the beginning of his tenure as Chairman, and certainly was during his time as a Governor (2002-05). And the supremely-confident Fed Chairman has argued that this has come without any cost to macroeconomic stability: after all, consumer price inflation is quiescent in the U.S., interest rates have remained at historic lows for years, and the U.S. dollar may well be in increasing demand for years to come around the globe. With a mild immodesty Mr. Bernanke waves off the Fed’s balance sheet explosion, saying that it was necessary along with all the Fed’s extraordinary actions in recent years, all of which averted a far-worse catastrophe than what actually occurred. Further, the balance sheet expansion has helped to stabilize and even recapitalize the U.S. commercial banking system, which looks solid now in comparison to China, Europe, or Japan. And the debt downgrade, after all, is the Treasury’s fault, not his; in the event, long term interest rates have actually fallen since last summer.

Implicitly, then, the Fed is steering its usual course between the “Scylla” of recession (in which commercial banks are propped up via the central bank’s absorbing of over-valued assets, and the Fed’s increasing of liquidity in order to promote lending activity that drives commerce and job creation), and the “Charybdis” of inflation. Indeed, Mr. Bernanke remains firm in his belief that inflation can be tamed via the tools the modern Fed now employs (including payment of interest on reserves and international swapping arrangements, as well as reserve requirement manipulation, discount rate policy, and open market operations), as well as the inherent leverage that is available to the global reserve currency. While strong growth may now prove elusive because of the extraordinary imbalances in the global economy and pronounced debt over-hang, the Fed’s solons continue to insist that they have and will avert any further disasters.

The Problems with Bernanke’s Thesis and Current Fed Policy

The fact is, however, current Fed policy may well be brewing further troubles, rather than averting them. To see this, consider the U.S. macro-economy, as does economist Frank Shostak, to be akin to a global multinational firm, consisting of several operating divisions like, say, the General Electric Company, the large conglomerate with $147 billion in revenue, in dozens of different businesses ranging from aircraft engines to major appliances to health care. What if the Federal Reserve were the funding agent for GE, and in a review of its (roughly) 40 different businesses, determined that 35 of them were profitable, and five of them unprofitable? Prudent management would dictate the shuttering of the five unprofitable lines of business, thereby increasing the return on capital of the business as a whole, and strengthening the firm’s balance sheet.

But if the Federal Reserve were more concerned with stoking commercial activity and employment, it may well decide to fund the five unprofitable businesses, both “directly” out of the profits of the other profitable divisions, as well as “indirectly” via borrowing and extending credit to the firm as a whole. It is important to understand that this could in theory go on for a very long time; indeed it could continue for as long as there were profits available to take from the other business units, both for direct use in the failing businesses as well as to support loans granted to the company as a whole. And the firm as a whole might well also continue to grow in revenues and profits. But real wealth would also be continually destroyed, in subsidizing and “carrying” the five unprofitable business units. The wealth of the owners, expressed as capital asset prices, would also be compromised, and returns to capital less than they otherwise would be.

Eventually, there may come a time when the profits of the other 35 businesses shrink, or are no longer enough to obtain credit to carry the unprofitable business units; this is when the firm will collapse. In a real sense, this is exactly the point that has been reached in Greece, and now fast approaches for Spain and Portugal: in all these countries, the productive classes are no longer big or numerous enough to carry or support the unproductive. Current fiscal imbalances guarantee that Greece-like collapse and insolvency will happen during the 21st century in the United States, too, if the bond market does not implode first, bring down the economy with it.

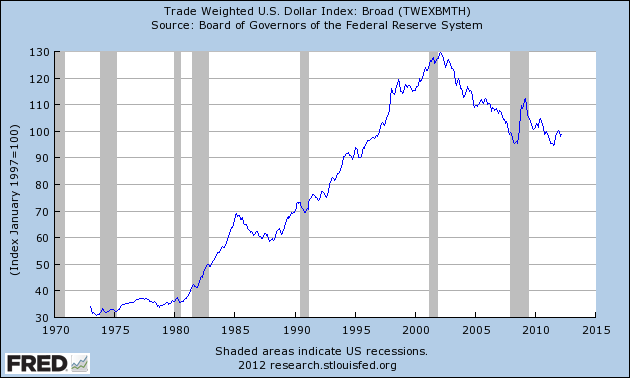

One way to gauge the extent of danger along these lines is to track the value of the U.S. dollar on international markets. The following chart shows the trade-weighted value of the dollar on currency markets dating to 1973:

Chart I. Trade-Weighted Value of the U.S. Dollar, 1973-Present

Source: Federal Reserve. Trading partner currencies include those from the Euro Area, Canada, Japan, Mexico, China, United Kingdom, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Brazil, Switzerland, Thailand, Philippines, Australia, Indonesia, India, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Sweden, Argentina, Venezuela, Chile and Colombia.

What the graph clearly shows is that the dollar began to firm immediately with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1981, and while it fell after the planned devaluation from the Plaza Accords in 1985 (one of Mr. Reagan’s bigger policy mistakes, undertaken at the behest of Treasury Secretary James Baker), it soon resumed a period of rising strength that ended only in 2002, and the Bush 43 Administration’s policy of dollar neglect coupled with a period of extraordinary Fed easing.

This chart, had it begun in 1970, would have shown a sharp drop in the value of the dollar in the early 70s, ratified by the closing of the gold window and move to a fully 100% fiat currency. But the key take-away from it is that the dollar’s value was not defended in the 1970s and early 80s, nor was it again after the election of President George W. Bush and his choice of three successive Treasury Secretaries (O’Neill, Snow, and Paulson) who preferred a weak dollar and export growth.

In the 1980s-90s, however, successive Administrations had Treasury Secretaries committed to a stronger dollar, and particularly in the cases of Reagan and Clinton, domestic discretionary spending growth was both fought and curtailed. That is to say, the value of the dollar correlates strongly with the degree to which the government’s “footprint” in the U.S. economy, best expressed as total federal spending as a percentage of GDP, is rising or falling. During the Reagan and Clinton eras, the federal spending/GDP ratio was falling for most of their combined 16 years, and indeed, at the end of the Clinton era was at 18.2%, the lowest percentage since the advent of the Great Society. During the 1970s and across much of the Bush 43 and Obama eras, the ratio of federal spending to GDP has been rising (now up to nearly 24%) – along with a falling dollar.

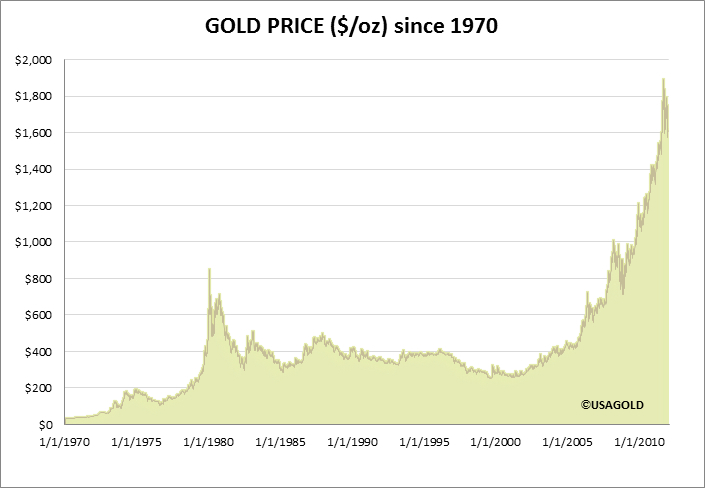

An obverse way of seeing much the same phenomena can be seen in the dollar price of gold, as shown in the following chart, since 1970:

Chart II. Gold Price in Ounces, 1971-Present

Here again, through much of the 1970s and 2000s, the gold price was rising; during the 1980s and 1990s, it was falling or stable, a sure sign of ramped-up real investment in the U.S. economy (and note, as a general matter, the inverse relationship between the price of gold and the value of the dollar between the two charts above).

Summary and Conclusions for Monetary Policy

The history cited above is basic, and indeed manifest in its obvious lessons. The Federal Reserve is now actively supporting and is in sympathy with an out-of-control public fisc; that is, the Fed is ratifying the Treasury’s profligacy. Mr. Bernanke’s focus on consumer price stability misses the larger point; dollar creation has led to international dollar flooding via demand for the reserve currency in an uncertain world. In the market that matters, the global market for goods and services, the U.S. dollar buys less, systematically, over time. This fact is now known to international investors, who have curtailed investment here after its 2006 peak – a fact of primal importance to future job creation in the United States.

A central bank, especially one running the global reserve currency, is handicapped in responding to “price signals” (via interest rate movements, in this case) in a way a free banking regime would not be. That is to say, if in times of uncertainty such as the 2008 financial crisis the demand for money were to increase (resulting in a declining velocity of circulation, or “V”, in the MV=PY equation of exchange), free banks would issue notes to match the demand of their customers, stabilizing nominal income (PY) and thus mitigating any employment losses. But they would not over-issue due to the constraints on their reserves and threat of redemption requests for (gold) cash. Commercial banks, however, operating under the aegis of a central bank running a fiat currency, have no such feedback mechanism from the market in place. Over-issuance – and currency depreciation – is quite common in such policy regimes.

Further, in a free banking regime, the government could not systematically run chronic budget deficits on up to the point of collapse, as in Greece and Spain now, and the U.S. in the near future. For if the government wanted to increase spending, it would have to raise taxes on its citizens, or failing that, issue bonds through the banking system. But in a free banking framework, this would drive up interest rates immediately, thereby acting as a brake, and limiting government spending volumes. But with a pliant central bank, the government can issue new bonds indefinitely, as is happening now. (Of course we recognize that Mr. Bernanke must deal with the world “as it is.” But he could refuse to cooperate with and ratify the insane levels of fiscal profligacy witnessed in the U.S. in the last decade; he could, instead, announce a commitment to make the U.S. dollar the strongest currency in the world, as befits a global reserve currency. This would entail a gradual but systematic burn-down of the Fed’s Treasury portfolio, and relinquishment of its mortgage-backed assets over time as well. An express policy to whittle down the price of commodities, including gold, could also be pursued. Leadership at the Fed would in turn stiffen spine in Congress with respect to making hard spending choices. All of this would lead to a rising dollar and rising capital investment in the U.S. — and with that, increasing levels of employment.)

In our view the current Bernanky policy mix is all a slow-motion tragedy, as “chickens most assuredly come home to roost.” To be sure, in the short run, equity investors applaud the Fed’s pumping as much as bond markets do; surely some of the excess liquidity in the banking system, thanks to the new credit creation, makes its way into equity markets, propping up prices – including those representing bad business concepts which might be unprofitable and should be liquidated. But like the 1999-2000 dot-com bubble, the rise in equity prices is both excessive and unstable. Periodic corrections (like the 1970s) are unavoidable, and absent a policy mix which both supports sustainable economic growth and defends the value of the dollar (the latter, indeed, is implied by the former), U.S. equity markets are in a quasi-permanent trading range, while the bond market teeters toward some form of collapse.

All of this portends several troubled years – decades? – of economic torpor in the time ahead. The one ray of hope at the moment is that the economic advisors to the likely Republican nominee understand all this, and in addition to planning for their friend Ben Bernanke’s retirement next year, they are drawing up the architecture for comprehensive monetary reform in the years ahead. Such reform, it is hoped, will resurrect the venerable saying about a dollar being “as good as gold.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch